Ancient Roots: The Origins of Chinese Alchemy

The first known alchemist was the Chinese Zou Yan (Tsou Yen), who lived at the same time that signs of alchemy arose in Babylon and Egypt, during the third and fourth centuries before the Western Christian Era.[1] In time, respected Chinese scholars, priests and even emperors, became deeply interested in alchemical pursuits. Visualization and breathing techniques prepared the empire, from crown to peasant, for ancient and timeless meditation, first described by some of the first Daoist philosophical texts.

The first collections of these instructional and inspirational texts were attributed to Laozi (Lao Tzu), who is supposed to have lived in the fifth century BCE, though the literature is dated no earlier than the middle of the fourth century BCE. The legendary Laozi’s Daode jing (Tao Te Ching), or Classic of the Way and Its Virtue, is also simply called the Laozi. It is a compilation of mature contemplations written as a guide addressed to a ruler.

Commentaries on the Laozi, notably the Xiang’er, Heshang gong and Wang Bi commentaries, increased its popularity. Following the Laozi was the Zhuangzi, fourth century BCE, and the fourth century CE text Liezi, attributed to a fifth century BCE philosopher mentioned by Zhuangzi. These three collections of writings are the primary texts of Daoist philosophy.

Many other Daoist works would follow, especially Huang-Lao texts, such as the second century BCE Huainanzi and various non-extant or recently discovered ancient manuscripts claiming to represent the words of the Yellow Emperor.[2] Huang-Lao Daoism refers to the metaphysical and legalist philosophical tradition attributed to the mythological Yellow Emperor and Laozi. Huang-Lao was the primary philosophy of the Han imperial court until it was replaced with Confucianism during the first century BCE.

[1] Lu-Chiang Wu, Tenney L. Davis and Wei Po-Yang. “An Ancient Chinese Treatise on Alchemy Entitled Ts’an T’ung Ch’i.” Isis Vol. 18, No. 2 (Oct., 1932). The University of Chicago Press. pp. 210-289.

[2] The ancient silk manuscripts discovered in 1973 at the Mawangdui site in Changsha, China, offer a glimpse into Huang-Lao philosophy. Early English translations include that of Robin D. S. Yates, Five Lost Classics: Tao, Huanglao, and Yin-Yang in Han China, Random House, Inc., New York, 1997.

Wang Bi maintained a secular Daoist philosophy

The ultimate origin of alchemy in China lay in the Daoist magicians. These recluses, from discussions on the Laozi, developed the idea of a hsien or human being made immortal through holistic lifestyle, meditation, breathing techniques, visualization, diet and drugs. It was natural that some would turn to the proto-science of alchemy in the attempt to chemically produce recipes for health and longevity or even an elixir of immortality.

Consequently, Daoist magicians used the elements and processes of the science of chemistry as symbols in their visualizations, which were preparations for meditation leading to the “embracing the One” of Laozi. Ironically, the fifty-fifth chapter of the Laozi states clearly, “Attempting to extend one’s lifespan (unnaturally) is a bad omen. To control the qi (breath/life-force) with the will- this is called forcing things.”

Early Chinese Alchemy: Enlightenment and Immortality

King Zheng of Qin (259 – 210 BCE), the founder of the Qin dynasty, called himself Qin Shi Huang, the “First Emperor of Qin,” in 220 BCE when he conquered the other Warring States and became the first emperor of a unified China. The Great Wall of China and the now famous Terracotta Warriors were built under his auspices. When he ascended the throne at age thirteen he began the construction of his own tomb. This project required 700,000 workers and thirty-eight years to complete.

The traditional Chinese belief is that replicas of property burned at a funeral or buried with the departed will pass into possession of the deceased in the afterlife. Within an area of 100 square kilometers of buried buildings is enclosed a walled city within a walled city, which contains a massive pyramid, over twice the volume of the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt. This pyramid was buried about seven meters deep and covered in foliage and trees. At the bottom of the pyramid, guarded by booby-traps armed with arrows, was the emperor’s tomb.

The Han Dynasty historian Sima Qian wrote: “Replicas of palaces, scenic towers, and the hundred officials, as well as rare utensils and wonderful objects, were brought to fill up the tomb. Craftsmen were ordered to set up crossbows and arrows, rigged so they would immediately shoot down anyone attempting to break in. Mercury was used to fashion imitations of the hundred rivers, the Yellow River and the Yangtze, and the seas, constructed in such a way that they seemed to flow. Above were representations of all the heavenly bodies, below, the features of the earth.”[1]

The Terracotta Warriors

The Terracotta Warriors are replicas of the emperor’s army, about 8,000 life-sized sculptures, placed within the mausoleum to accompany the emperor to the afterlife. Maidens were buried with the emperor to serve in his harem, as were the craftsmen who built his tomb, to keep its secrets secure. Believing in alchemy as a way to longevity, the emperor ingested mercury pills in his quest for an elixir of immortality which, ironically, killed him at the age of thirty-nine.[2] His tomb was completed just over a year after he died.

The Divine Laozi

In the Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) wandering ascetics who practiced magic and alchemy began to revere Laozi as an idealized alchemist and immortal with superhuman powers. This version of Laozi appears in the first collection of Daoist hagiographies, the Immortals’ Biographies of Liu Xiang (c. 79-8 BCE) and he appears in the Biographies of Spirit Immortals by Ko Hung (c. 283 – 343 CE.) By the end of the Tang dynasty, in the tenth century CE, internal alchemy had become the predominant paradigm in China.

During the second century CE Laozi became the personification of the Dao under the Huang-Lao school of the Han elite. Huang Di, the Yellow Emperor, and Laozi, were worshipped as the perfect ruler and the perfect sage, respectively. These god immortals were to usher in an era of Great Peace. Thus, Laozi was revered as a god, the embodiment of the Dao, who incarnated as the savior of humanity for his chosen people.

The oldest commentary to the Laozi, known as the Xiang’er commentary, was written in the second century CE for the Celestial Masters sect of religious Daoism. This was the first Daoist alchemical school to establish itself during the time China was becoming Daoist. It was founded by Zhang Daoling in 241 CE, who became the first Celestial Master after his revelations, and established a sovereign theocracy in what is now Sichuan.

About 420 CE arose the first religious myth surrounding the birth of Laozi. It was written in the Scripture of the Inner Explanation of the Three Heavens of the Celestial Masters sect. According to the scripture, Laozi is the embodiment of the Dao, who incarnated first as Laozi in China and secondly as the Buddha in India. Further scriptures describe mythological accounts of Laozi’s meeting with Yinzi, writing the Daode jing and journeying West.[3]

The Xiang’er commentary, which was and is to this day memorized and chanted as scripture, says, “Those who use qi and forcibly inhale and exhale do not harmonize with clarity and stillness and will not have longevity.” The ultimate goal is to lead a natural life and remain tranquil and pure, the mind a spontaneous void, ever embracing the One. The earliest alchemists in the world outside of China sought potions or medicine for longevity – but not for immortality – the archetypal quest for the elixir of immortality began in ancient China.

To symbolize the state of enlightenment the Daoists called immortality, the early Zhuangzi, Chuci (Songs of the South), and Liezi texts described enchanted islands, sacred mountains and otherworldly palaces. These were inhabited by perfected alchemists who became god-like by consuming elixir or magic mushrooms, and who would fly away on the back of a dragon to live in one of the heavenly realms. Later Daoists, epitomized by the wise Confucian Ge Hong (283 – 343 CE), interpreted immortality in a literal sense and described operative alchemical techniques for health, magical powers and longevity, as well as immortality.

Chapter Sixteen of the Laozi defines my own understanding of immortality:

“Emptiness- the utmost limit:

Tranquility- the center.[4]

All things arise together, side by side,

And I watch them return to repose.

They come forth and flourish

And each returns to its root.

To return to the root is tranquility and peace.

Tranquility is the return to one’s destiny.[5]

To know destiny is to be wise.

Not to know destiny is to be blind and reckless.

Being blind and reckless, one’s actions will lead to misfortune.

To know the eternal law is to be all-embracing;

To be all-embracing is to be impartial and just;

To be impartial and just is to be kingly;

To be kingly is to be like Heaven;

To be like Heaven is to be One with the Dao;

To be One with the Dao is to be immortal;

Such does not perish with mortal death.”

[1] Brian Dunning, “The Mercury Rivers of Emperor Qin Shi Huang,” Skeptoid, Podcast #566, 11 April, 2017, https://skeptoid.com/episodes/4566

[2] Clara Moskowitz, “The Secret Tomb of China’s 1st Emperor: Will We Ever See Inside?” Live Science, 17 Aug., 2012,

https://www.livescience.com/22454-ancient-chinese-tomb-terracotta-warriors.html

[3] Livia Kohn, “The Lao-Tzu Myth,” Lao-Tzu and the Tao-Te-Ching edited by Livia Kohn and Michael Lafargue, State University of New York Press, 1998.

[4] This is a direct instruction on meditation.

[5] “Destiny” may be translated as “eternal law.”

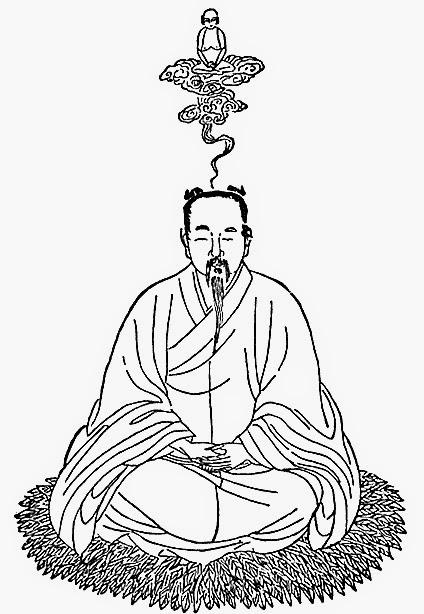

Laozi

The Alchemy of Magic and Religion

The several texts of the Taipingjing, or Scriptures of the Great Peace, appeared during the Han Dynasty (first century BCE – second century CE), espousing the yin-yang and five elements theories. This scripture greatly influenced Zhang Jue, the ringleader of the Yellow Turban Rebellion, and remains extant in the Daoist Canon (Daozang).

The idea of the Great Peace rested on the belief that human moral behavior held the balance of the natural world. Natural disasters and disease were caused by human sin, and the era of Great Peace would arrive when humans, under the leadership of Celestial Masters and benevolent rulers, cultivated the Dao and healed the mortal world. The Taipingjing, or Scriptures of the Great Peace, described the Guarding the One meditation and other meditations involving visualizations, most notably, colors corresponding with parts of the human anatomy.

Zhang Ling, a.k.a. Zhang Daoling (34 – 156 CE), was the founder of the Way of the Celestial Masters sect of Daoist religion. This sect was known derogatively as the Way of the Five Pecks of Rice for the fee it imposed on its members. Zhang was a magistrate who in his later years had a vision of Laozi, which convinced him to adopt the title Celestial Master, as he was to lead a chosen few into the era of Great Peace after a period of apocalyptic disaster. Zhang developed the first Daoist pantheon and gathered a following of adherents, which at one time controlled a theocratic state. The ancient lineage has persisted to the present day headed by leaders bearing the title of Celestial Master.

The founding of the Celestial Masters sect was followed by emergence of the Shangqing (“Supreme Clarity” or “Great Purity,” also known as the Mao Shan sect) and Lingbao (“Sacred Jewel”) traditions. These latter two schools borrowed much from the competing religion of Buddhism. The fourth and fifth century Mao Shan manuscripts, like those of Tao Hongjing, are the first texts to describe Daoist alchemical meditation techniques.

Daoist Immortals at Mount Zhongnan in Shaanxi Province: by tradition the mountain temple complex founded by Laozi after he wrote the Daode jing.

The Shangqing sect originated in the visions of Lady Wei (252 – 334) in the year 288 CE. Lady Wei was a priest in the Celestial Masters sect when she received the True Scripture of Great Profundity and other scriptures via her visions. Her Huangting jing, “Scripture of the Yellow Court,” placed gods and spirits within organs of the human anatomy and prescribed visualizations upon which to meditate for spiritual harmony. The content is similar to the third century Laozi zhongjing, or “Central Scripture of Laozi.”[1] These are some of the earliest instructional texts on Daoist meditation and inner alchemy.

The reader is referred to Taoist Meditation, the Mao-Shan Tradition of Great Purity, by Isabelle Robinet, published in 1979 in French and translated to English by Julian F. Pas and Norman J. Girardot, published by the State University of New York Press, Albany, 1993. This book teases its readers with descriptions of meditations from various sources within the Daoist Canon, including The Scripture of the Yellow Court, The Scripture of Great Profundity, “Meditation on the Four Directions,” “Chart of the True Form of the Five Peaks,” “The Scarlet Breath of the Red Furnace,” “Scripture of the March on the Net of Heaven,” “Jade Characters of the Golden Book,” Book of the Three Charts Which Open Heaven, and many others.

The Cantong Qi, “Kinship of the Three,” or “Triplex Unity,” attributed to the second century Wei Boyang, is an important work on Chinese inner alchemy. The text unifies the doctrines of the Yijing (I Ching), the Daoism of Laozi and Daoist alchemy.[2] The Shangqing “The Upper Scripture of the Purple Texts Inscribed by the Spirit” was revealed to Yang Xi (330 – 386) and included in the first collections of the Daoist Canon. This work describes lucid visions, symbolic alchemical visualization techniques, and the use of talismans. It includes sexual alchemy and Daoist magic.[3]

Examples of Daoist alchemical processes, including the shouyi, or “Guarding the One,” meditation may be explored in Jin Dynasty scholar and alchemist Ge Hung’s Baopuzi (Book of the Master Who Embraces Simplicity). Consult Alchemy, Medicine & Religion in the China of A.D. 320; the Nei P’ien of Ko Hung. Translated and Edited by James R. Ware. Dover Publications, Inc. New York. 1966. The Secret 9-Crucible Cinnabars of the Yellow Emperor is found on p. 75 and the Lord Lao Meditation is on p. 256.

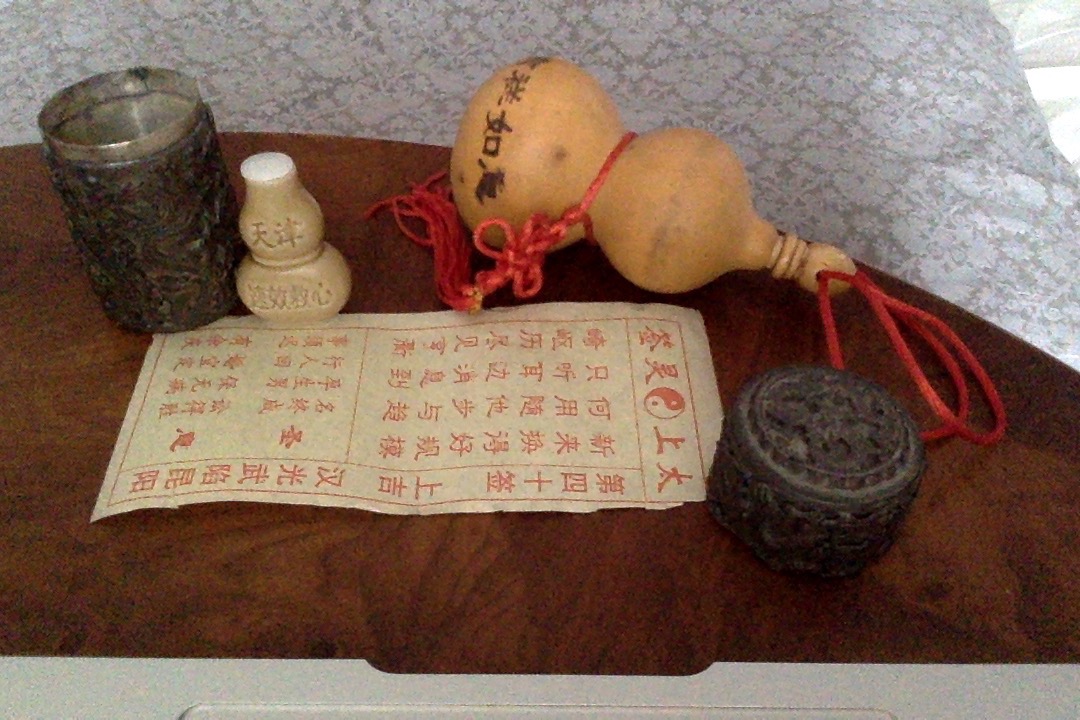

Daoist gourds, vessels of the elixir of immortality; and a fortune given by a Daoist monk.

The Lingbao (“Numinous Treasure”) school was formed around 400 CE. Ge Hong’s nephew, Ge Chaofu, produced Daoist scriptures Wufujing, “The Book of Five Talismans” which he claimed had been passed down from Ge Xuan, the great uncle of Ge Hong. The Lingbao sect blended Buddhist ideas into the native Chinese Daoist religion, such as certain elements of cosmology and the belief in reincarnation. It borrowed largely from Shangqing scriptures and Celestial Masters sect ritual.

During the Tang Dynasty (618 – 907) the competition between the Daoist and Buddhist religions caused both traditions to develop new methods and adopt aspects of the other’s beliefs and practices. This period saw the proliferation of Vajrayana Buddhist Tantras and Daoist classics on meditation.

Notable among the Tang Daoist texts were the Cunshen lianqi ming, or “Inscription on Visualization of Spirit and Refinement of Energy” by Sun Simiao, the Zuowanglun, or “Essay on Sitting in Forgetfulness,’ of Sima Chengzhen, and the Shenxian kexue lun, “Essay on How One May Become a Divine Immortal through Training,” by Wu Yun. These works focused on concentration, cosmology, visualization and absorption in the Dao. The ninth century Daoist Qingjing Jing, “Classic of Purity and Stillness,” combines Daoist guan, or observational meditation, and Buddhist Vippasana, or insight meditation.

Michael Saso’s Taoist Master Chuang, (Sacred Mountain Press, Eldorado Springs, CO, 2000) describes interesting alchemical meditations and rituals, including Thunder Magic from the Pole Star sect of Mount Wudang. His classification of “orthodox” and “unorthodox” teachings has come under some scholarly criticism, but his contribution is significant, nonetheless.

Daoist Thunder Magic involved deities, spirits, magic ritual, incantations, exorcism, mudras and talismans. It was first mentioned in writing in the Taishang Dongyuan Shenzhou Jing, or The Book of Divine Incantations of the Supreme Pervasive Abyss, which was prefaced by the Daoist priest Du Guangting (850 – 933). Thunder Magic was an integral aspect of the Celestial Master sect by the twelfth century.[4]

Xuantian Shangdi (Zhenwu), god of the North. Ithaca: Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art.

For examples of Daoist alchemical meditation, see “Chinese Daoist Alchemical Meditation” at Science Abbey.

Operative alchemy in China began in the Western Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 24 CE) as a synthesis of metallurgy and chemistry, and drove the Emperor to ban the manufacture of counterfeit gold. Huan Tan (43 BCE – 28 CE) asserts in his Hsin-Lun, New Treatise, the existence of a preparation that transforms quicksilver into silver.

Liu Xiang (79 – 8 BCE) was a great intellectual and author of the time, compiler of the first imperial library catalog, and traditionally incorrectly assumed to be the author of the Daoist Biographies of the Immortals. He vouched for an alchemist’s claims to have transmuted base metals to gold and, unable to repeat the process, Liu Xiang was humiliated.

During the Eastern Han Dynasty, Wei Boyang, an alchemist and author of The Kinship of the Three, was the first to publish the chemical structure of gunpowder. A pseudonymous writing from the early second century CE attributed to him describes a recipe for an elixir of life based on the Yijing (Classic of Changes) and the philosophy that a mortal may consume a tincture with gold to become an immortal.

It is most likely that symbolic alchemy passed from China to the Persian Magi. These Magi had contact with the Chinese long before the Islamic conquest of Persia (modern day Iran). Pre-Islamic period Arab philosophers learned internal alchemy from the Persian Magi, disciples of Zoroaster (or Zarathustra), prophet of Ahura Mazda, and brought the ideas to Greece, where alchemy was being practiced by the first century prior to the Christian era.

About this time in Asia, there were ideas of transmuting base metals into gold in Buddhist texts, forming an alchemical conception of a much older tradition of meditation in India. Later, being grounded in a global alchemical tradition, Arab aristocrats studied the Laozi meditation of the famous fourth century alchemist Ge Hong and other Chinese alchemical texts. It was through these Arab scholars and scientists that Europeans first encountered the ancient knowledge of both East and West, which sparked the illumination of the Renaissance period.

Carl Gustav Jung (1875 – 1961) was a Swiss student of the founder of modern psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud. He developed his own system of psychotherapy that rivaled Freud’s from its inception. The Secret of the Golden Flower was written during the Qing Dynasty (1644 – 1912) by either Lü Dongbin, or his student Wang Chongyang, the founder of the Quanzhen School of religious alchemical Daoism.

The Secret of the Golden Flower is a Chinese Daoist technical manual of meditation teaching the techniques of sitting silently, breathing and contemplation. The book was translated to German by Richard Wilhelm in 1929 with a commentary by Carl Jung, a personal friend of Wilhelm’s. It was this book that piqued Jung’s interest in alchemy and inspired his psychoanalytical methods, which are still in use today.[5] It is clear by this that Chinese alchemy’s influence has reached even into the modern medical science of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

[1] http://www.goldenelixir.com/taoism/texts_laozi_zhongjing.html

[2] http://www.goldenelixir.com/jindan/zyctq.html

[3] Early Daoist Scriptures. Stephen R. Bokenkamp. University of California Press. 1997, p. 275.

[4] Scriptures, Schools and Forms of Practice in Daoism: A Berlin Symposium, edited by Poul Andersen, Florian C. Reiter, Harrassowitz Verlog, Weissbadden 2005, pp. 97 – 114.

[5] The Secret of the Golden Flower (T’ai I Chin Hua Tsung Chih) was Translated by Richard Wilhelm; Translated from German by Cary F. Baynes; Published by Kegan Paul, Trench and Trubner (1931); Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd (1965): http://www.spiritandflesh.com/Chinese_SecretoftheGoldenFlower_online.htm

Steps of Chinese Alchemy

Like Western alchemy, Daoist alchemical operations could follow any number of steps. Whereas alchemy in the West often followed a seven or twelve stepped process, Charles Luk described a procedure of eight operations from The Secrets of Cultivation of Essential Nature and Eternal Life, written by Zhao Bichen, or Chao Pi Ch’en (1860 – 1953.)

Charles Luk made Chinese symbolic alchemy accessible to English readers by decoding the original alchemical symbolism to terms more properly belonging to Traditional Chinese Medicine. It is the future task of modern science to further decode these claims into scientific language and provide notes on the real processes at work in these spiritual exercises.

The Daoist Wong Tai Sin temple in Hong Kong

The goal of the Chinese alchemist is to produce the elixir of life, the dew of immortality, Cinnabar or Mercury, which may be made into a pill to be digested. This process, or Way of life, is comparable to the Western alchemical Great Work, the creation of the mercurial elixir or alchemical powder of the sun, the Philosopher’s Stone.

This operation creates, in the language of alchemy, a spiritual fetus, astral body or invisible body, which allows the alchemist to travel to unexplored territories of the psyche, and opens the doors of perception to new dimensions. It is a way to commune with one’s inner guide or true self whilst in the flesh. The alchemist reunites with the “profane” world and polite society in order to improve or “spiritualize” his own environment, and will withdraw into meditation or pure observation again, in an endless cycle. This is the perpetual process that underlies alchemical immortality or illumination.

As preparation, ideally the alchemist will have a quiet hut or temple not too far from a town or city, a meditation seat, money for food, etc., and companions with whom to practice alchemy. The goal of the alchemist is to return to the pure positive state of infancy, the ultimate psychological expression of wu-wei, “inaction” or natural being. Ideally, he begins alchemical work at age sixteen when he matures and, through passion, learning and acting in the world, begins to deplete his life-force. Thus, in return, he fulfills the cycle of Taiji in the span of his life.

The first operation is the Conservation of the “Three Treasures,” Jing, Qi, and Shen, each which represent a kind of spirit. The practice of Daoist alchemy begins with self-restraint, moderation and stillness. The alchemist learns to control the heart, the seat of fire, that it may not be stirred by the seven emotions: pleasure, anger, sorrow, joy, love, hate, desire; or the five thieves: eye, ear, nose, tongue, body. This is the foundation of the preservation and growth of jing, or generative force, which is dispersed by the sense and emotions.

According to the second chapter of the Daode jing, the One gives birth to the two (yin and yang), the two to the three (jing, qi, shen), and the three to the 10,000 things (an archaic Chinese term for the totality of all things in the universe.) This is the progressive degeneration of Creation, which is completed only by the Return, whereby the alchemist transmutes the jing, qi and shen in his physical body and the inner universe returns to Dao.

The alchemist returns to the state of an infant, no-mind, at one with Dao and manifesting wu-wei. Cultivating the Three Treasures thus leads to Taoist Immortality. Cultivating jing, or essence, leads to a store of generative energy. Cultivating qi, life-force or vitality, leads to the realization of eternal life. Cultivating shen, or spirit, leads to the realization of essential nature.

The second stage is the Restoration of Jing. Course jing is contained in the semen and wasting it depletes the Three Treasures. Retention of the semen and cultivation of tranquility allows jing and Qi to flow from the ‘three receptacles’ (brain or head, heart and Base or “Kidneys”) into the “psychic channels.” The Base (and by implication, the genitals) is called the “Gateway of Life.”

Lust drains jing and Qi from the proper paths to the Gateway of Life, wasting them. Still, extremes are to be avoided; pure abstinence is not to be expected, even in older people. In conservation of the jing, desires, especially lust, must be refined to moderation. As for the reparation and retention of jing, a healthy lifestyle free from strong passions will repair depletions of jing and Qi, from an earlier life without the benefits of alchemy.

Alcohol and strong seasonings on food ought to be avoided; the diet must be plain and nutritious, mainly vegetables; and one should engage in moderate exercise such as Taijiquan. This is called “collecting jing” or “gathering jing.” The alchemical exercise for gathering jing is the practice of transmuting shin to jing.

Stage three is the Transmutation of Jing. Course jing is related to blood and semen. Subtle jing is produced from course ching when ejaculation is restrained, desires and sensations are stilled, thoughts are stilled, and consciousness rests in stillness. One returns to this state of tranquility with meditation on the light of the Precious Square Inch, or Third Eye, the space between and slightly above the eyes.

Cosmic jing is the formative force in the body. Emptying the mind settles the chi and jing is produced; yang-chi (pure cosmic vitality, the De of Dao or virtue of the Way) gathers in the mind and nourishes jing. Yang-shen (cosmic shen, a property of Dao, itself) flows in through the Third Eye, reaches its peak and becomes “contained” because the entrances of all the body’s senses and psychic cavities are sealed off and guarded. Course jing is gross and impure, while subtle jing is fine and uncontaminated, so nourishing and purifying course jing transmutes it into subtle jing.

The fourth step is Nourishment of Qi. Nourishing Qi means accumulating a full store of subtle Qi. Course Qi is in the breath. Subtle Qi is potential energy. For this, the passions must be stilled, and the breath is used to nourish the course and subtle Qis. Passions refer to anger, desire, intoxication or any immoderate emotion. Subtle Qi is collected thru the proper interaction of the Three Treasures. Subtle Qi is then transmuted into yang-shen (pure cosmic spirit), bringing the alchemist to merge with Dao, the limitless Source of Being. Shen, our nature, and Qi, our life, are tied to breath control. This is the operation of Qigong, the Macrocosmic and the Microcosmic Orbit, as described above.

The fifth stage is Transmutation of Qi. The heart of Daoist alchemy resides in techniques to transmute Qi to shen, such as “Transmute Jing to Void.” The Cavity of the Dragon or Lower Elixir Field (Dantien) is the seat of the vital force (jing) and element of water. This is the center of gravity, about two or three inches below the naval. The Heart is the seat of the spirit (shen) and the element of fire. The alchemical operation is the concentration on the Cavity of the Dragon, drawing the fire down into the water, and drawing the steam upward.

The Lower Elixir Field is visualized as a stove under a cauldron of generative force (jing Qi). The cauldron itself is visualized to rise while the stove remains. The cauldron begins in the Lower Elixir Field to gather generative force (jing), then moves to the “Middle Elixir Field” in the solar plexus to transmute jing to Qi, then moves to the “Upper Elixir Field” in the brain to transmute ji to shen.

In the sixth stage, the Nourishment of Shen, the alchemist concentrates the course shen in the body. This causes Qi to gather and nourishes the jing. This is done by concentrating the mind, free of thoughts and desire, so it becomes pure spirit. Late at night, without fixed postures, hands are folded together, all is relaxed, and the alchemist focuses the mind on nothing but the body. The alchemist lets the mind be still but controls it so one’s own body is the sole object of its attention. The senses are banished.

During the seventh operation, the Transmutation of Shen, course shen is completely transformed to subtle shen. Even the body is forgotten. Nothing remains but pure awareness.

The eighth and final process is Transmutation of Cosmic Shen to Void (Dao). The illusionary individual self makes the ‘Return to the Source.’ The generative force, vitality and spirit are united to form the spiritual embryo. Thus course jing has been made subtle: subtle jing has been used to transmute course chi to subtle Qi; subtle jing and subtle Qi have been used together to transmute course shen into subtle shen; which has been made into void. A spirit embryo has been created which can return to the Dao.

When the alchemist is ready to “stop the fire”, or stop practicing the technique of the microcosmic orbit, he is ready to go to a mountain to train “stopping fire” to collect the macrocosmic alchemical agent, circulating heart, spirit, and thought instead of jing and Qi. He will have visions of heavens and hells, and women and girls. He must focus on the Third Eye and hold onto the One. The adept is ready to sacrifice his body for immortality. The adept reverses the way of the world.

The creation of the Immortal Fetus begins with the five vital breaths activating the five organs (Water – north, body/generative force; Fire – south, heart/breath; Wood – east, essential nature/incorporeal soul; Metal – west, passions/corporeal soul; Earth – center) and coalesce in the head as a cross or pentagram of light. This light (yin) unites with the golden light of Qi (life-force) in the union of the positive (light/yang) and the negative (yin) principles, and the immortal fetus is created. Like a real fetus, it is said to take nine to ten months to complete.

In the next visualization, the immortal fetus must be lifted to the brain, rise out of the crown of the head, and returned to the body via the Third Eye. The vital breaths of the Twelve Functions and Organs of Traditional Chinese Medicine are concentrated in the head. Then, when one is united as one with the fetus, the fetus is forgotten, and there is only positive prenatal spirit, one leaves the mortal body from the crown of the head, stirred by the thought of emptiness.

As the immortal fetus, or rather, the positive prenatal spirit, the Daoist rises out of his head into the void and the universe. The Invisible Body leaves the body by opening the gate at the top of the head. Finally, the positive spirit should be returned to its original cavity, the Third Eye, where the serene alchemist rests his concentration until the four elements disperse and all is annihilated.

Magical powers are said to be attained when the immortal fetus is fully developed, and Spirit is wholly positive.

- Stoppage of all drain of vital and generative forces

- Divine sight – to see things in heaven

- Divine hearing – to hear voices

- Knowledge of past lives

- Understanding other minds – knowing the thoughts of others and predicting the future

- The divine mirror – visions on a magic mirror or crystal ball

The skeptic will doubt the veracity of accounts and claims regarding these alleged powers. Science cannot prove a negative but it can investigate and disprove any such supernatural assertions. Some ancient visualization and breathing techniques are still useful today, informing our present methods of meditation. Effective alchemy will always align with science.

Taoist Mysteries and Magic by John Blofeld is a fun read.