The Vitruvian Tradition

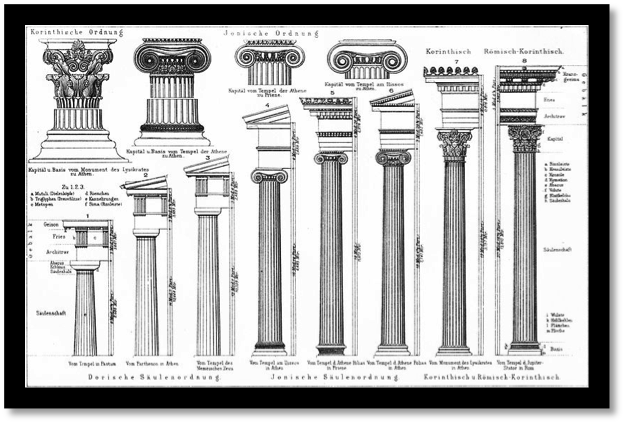

The liberal arts were based upon the Hellenistic education called enkyklios paideia, taught by fifth century BCE Sophists to the upper classes, and promoted by Roman luminaries like Cicero. The Classical Roman architect Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (80 BCE – 15 CE), who was raised in the early liberal arts tradition, admonished the architect that expertise arose from both practice and reasoning.

In his Ten Books on Architecture Vitruvius wrote that due to the broad range of skills required to build excellent architectural structures, architects must be educated from an early age to master all the arts, especially letters, before reaching the loftiest art of Architecture.[1]

Vitruvius suggested the studies of letters, draftsmanship, geometry, optics, arithmetic, history, philosophy, physiology, music, medicine, law, and astronomy. Moral philosophy complemented natural philosophy. Medicine, following Galen, was the attempt to understand and manipulate the four natural elements and the four “humors” of the body, to achieve a balance, or health, where disorders were considered imbalances.

Architecture was a kind of extension of Medicine, and Vitruvius relied heavily on the philosophy of the four elements of earth, water, air, fire. The philosophy originated with Ionian philosophers beginning in the sixth century BCE, but Vitruvius attributed the first full expression of this philosophy to Pythagoras.[2]

Pythagoras did follow this philosophy, as did those who admired him, like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. Thus, the learning passed through both the architects and the institutions of higher learning of the philosophers, such as the Pythagoreans, the Neo-Platonists and the Academy.

Saint Peter’s Basilica, Rome, Italy

The Vitruvian tradition was carried into Europe in the sixth century through a group of Italian stonemasons who lived in Lombardy, near Lake Como. These Como Masons or Comacines were presumably descended from the College of Masons (Collegium) at Rome, which thrived during the Empire to even as late as the Emperors Constantine and Theodosius in the fourth and fifth centuries. They fled Rome for Lombardy when Rome was sacked by the barbarians, and formed what would become a very important guild in Europe.[3]

It has been suggested that the Collegium independently influenced the Anglo-Saxon architects. Evidence exists to place Collegia in Britain following the Roman conquest, especially with the reign of the Emperor Claudius, who first subjected the island. In the seventh century, the architectural style of the Anglo Saxons shows evidence of links with the Comacines.

According to Masonic historian Leader Scott (1837-1902), the Comacines may have influenced the Irish in the time of Saint Patrick, the French in the time of Charlemagne, the Germans (or Goths) in the ninth century, and the Normans in the tenth century.[4]

There is little hard evidence for these theories, but they are not altogether unfounded, as some such process must have occurred as the Roman Church penetrated Western Europe, bringing Cathedrals and Cathedral builders with it. During this time, prominent Church figures like Saint Augustine and secular Roman leaders like Boethius promoted and refined the liberal arts tradition.

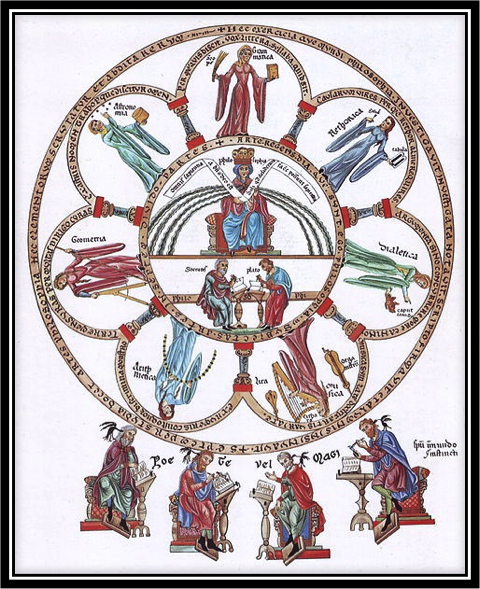

Hortus Deliciarum by Herrad von Landsberg, circa 1180.

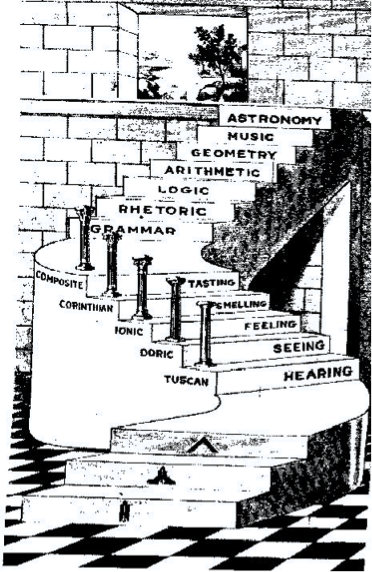

The Liberal Arts

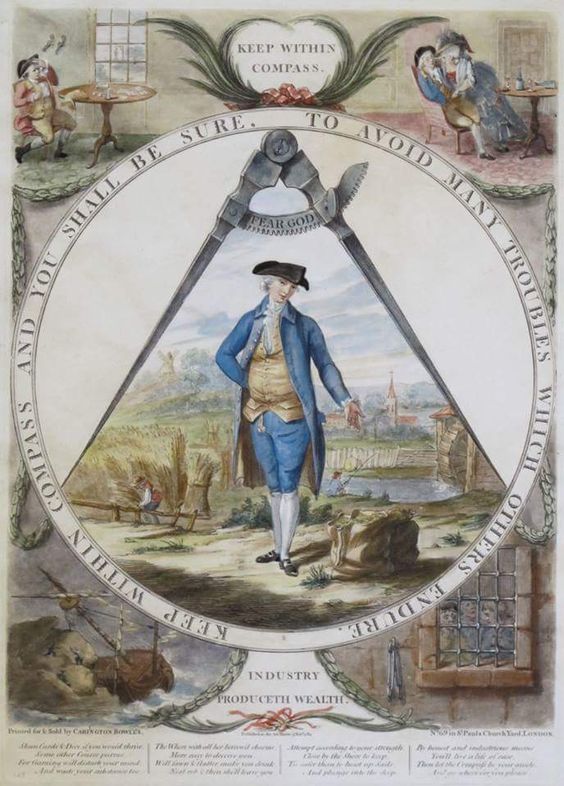

The Seven Liberal Arts were codified before the Common Era and by the Middle Ages represented the whole canon of education. The four mathematical arts were divided as the Pythagoreans had determined, into Arithmetic, Geometry, Music, and Astronomy. The other three arts were Logic, Grammar, and Rhetoric. Philosophy was considered to encompass and unite these branches of knowledge.

The liberal arts literally were the arts of freedom, which were practiced by free men as opposed to slaves, but as learned skills the liberal arts formed a discipline that freed men from ignorance, prejudice, and unchecked passion.[5]

In Europe, young men proceeded to university when they had completed their study of the trivium – the preparatory arts of grammar, rhetoric and dialectic or logic – and the quadrivium: arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy. The liberal arts and science are crowned by the philosophy of speculative or inner alchemy. The physics that the student learns in school takes on meaning only after more mature philosophical reflection.

The labors of observation, calculation and theory are essential, but the deeper aspect of physics, and indeed the whole of scientific exploration, is the state of understanding. In physics, understanding is enhanced by the philosophical studies of metaphysics, ethics and political philosophy. The deeper questions of biology, psychology and logic are all answered only in the investigation of philosophical principles.

Inner alchemy, unlike modern science, comprehends and organizes all branches of study, bringing everything under the umbrellas of humanism and the insight of meditation. A complete education must include the liberal arts, humanities, modern science and a holistic worldview. Symbolic alchemy and the liberal arts comprised the holistic worldview at the foundation of Freemasonry and modern science and they are just as necessary today.

Castle Belvoir, Leicestershire, England

the Origins of Masonic Knowledge

Architects in the Middle Ages were expected to possess this kind of education when they were designing and supervising the building of the great castles and cathedrals of Europe. When Masonic guilds were first formed in Europe, their creators were sure to introduce the most ancient examples of erudition into their pantheon of forebears. Because architects considered the ancient mathematicians like Pythagoras and Euclid to be their predecessors, Masonic histories and initiation ceremonies could include such references to antiquity.

Claims to such ancient origins appear in the “Regius Poem” about 1390, the first known document with Masonic references, as well as the “Old Charges” and later “Constitutions of the Freemasons.” The “Regius Poem” (Lines 53- 62) permits that:

“On thys maner, throe good wytte of geometry,

Bygan furst the craft of masonry:

The clerk Euclyde on thys wyse hyt fonde,

Thys craft of geometry yn Egypte londe.

Yn Egypte he taweghte hyt ful wyde,

Yn dyvers londe on every side;

Mony erys populariz, y understonde,

Eer that the craft com ynto thys londe.

Thys craft com ynto Englond, as y Eow say,

Yn tyme of good kynge Adelstonus day.” [6]

Lines 551 thru 564 of the same poem explain (not exactly accurately) that Euclid taught the “syens seven:” Gramatica, Dialetica, Rhethorica, Musica, Astromia, Arsmetica, and Gemetria, as well as Gramer[7] which, nonetheless, indicate the importance of the liberal arts in the early Masonic craft guilds.

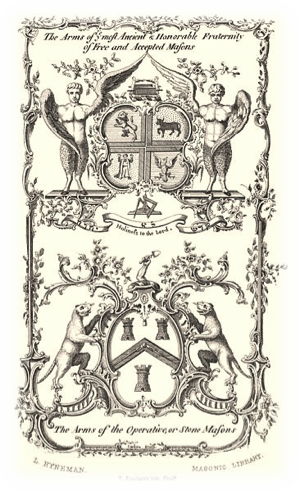

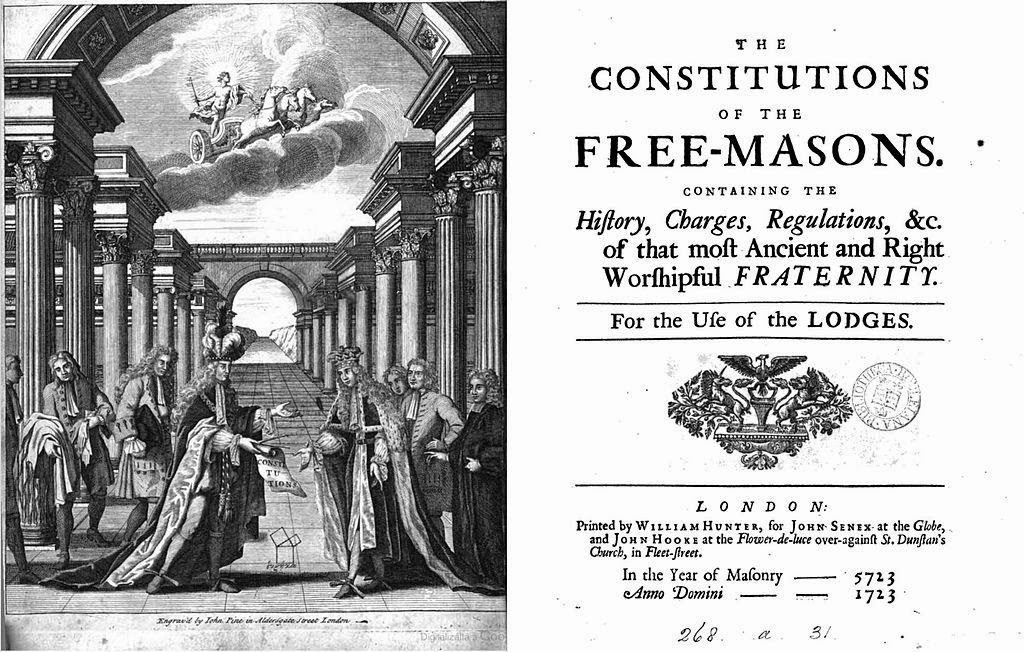

The First Masonic Constitutions

In 1723 James Anderson, the compiler of the first Grand Lodge Constitution, referred to the Old Charges as the “Gothic Constitutions.” They were named after the Goths that sacked the Roman Empire. Anderson and his contemporaries considered the Gothic architecture crude and barbaric, unlike the Classical architecture built under or inspired by the Roman Empire.

These “Gothic Constitutions” were scattered about England, in the hands of various lodges, until the Grand Master requested their use for the creation of a new Book of Constitutions in 1718, one year after the formation of the first Grand Lodge. As mentioned above, these had evolved from the mid fourteenth and seventeenth centuries with connections to both operative and speculative Masonic lodges.

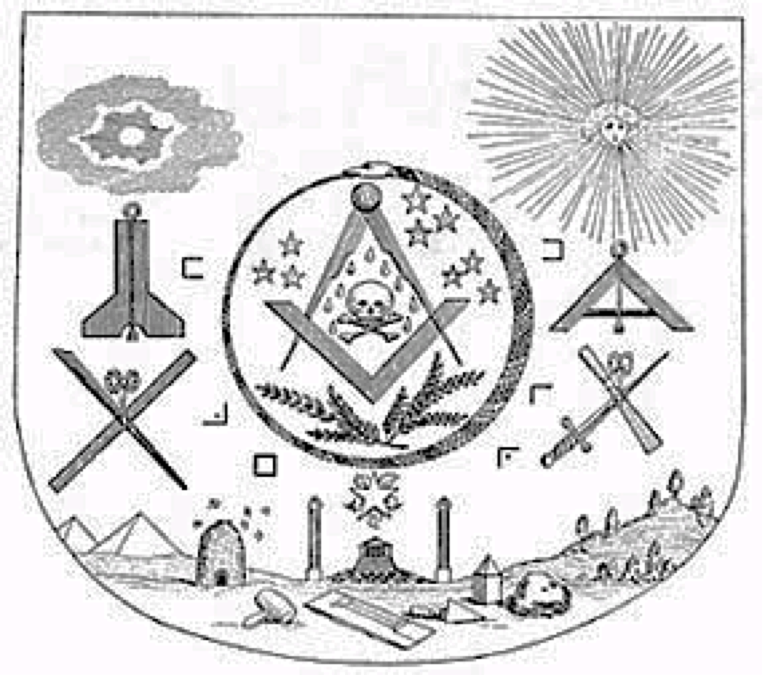

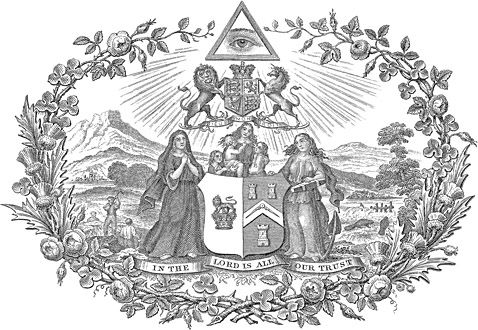

The Old Charges generally begin with an invocation of the Holy Trinity, and continue with the tradition of the Liberal Sciences: “Grammar,” “Rhetorick,” “Logick,” “Arithmetick,” “Musick,” “Astronomy,” and finally “Geometry,” which replaces Philosophy as the science that contains them all.

The authors of the Old Charges then trace the origins of masonry back to the period before Noah’s flood, to Lamech and his four children, who discovered all the crafts of the world, and thereon through Biblical personages up to Solomon and King Hiram, with the insertion of two non-biblical figures, Hermes (Trismegistus) and Euclid. The line is traced thru Charles Martel of France, Saint Alban of England and King Aethelstan of England.

The inclusion of Hermes in the Old Charges indicates an esoteric strain within speculative Freemasonry as it emerged from operative lodges. Another strain appears in Anderson’s Constitutions in 1723, with the mention of the Chaldeans, the Magi, and Pythagoras. A brief consideration of these references may shed some light on the official esoteric origins of Freemasonry as they were understood in early eighteenth century England and Scotland. Other, less direct, esoteric influences were to find their way into Freemasonry, as well, but these must be discussed separately.

Anderson added his own speculations, bringing the origin of Masonry back to Adam, the first man, himself. He alludes to the “Chaldees,” presumably the Chaldean astrologers, and the Magi. He evokes the builders of the Egyptian pyramids, and Greek and Roman architecture. He introduces Hiram Abif, Pythagoras, Archimedes, and Vitruvius, among others, and names Augustus Caesar Grandmaster of the Lodge at Rome.

Anderson bewails the destruction of the Roman Empire at the hands of the Goths and Vandals. He then gives a brief survey of English history to his own day, making many prominent monarchs and other individuals Masons along the way. Anderson viewed Freemasonry as a pillar of civilization and he invented a history to support this interpretation of the fraternity. As seekers of truth, we cannot condone his method in modern times, but we can admire his efforts. His Constitution became the foundation of modern Freemasonry, an institution designed, like the liberal arts, to edify and enlighten humankind for all time.

Operative Freemasonry

The Normans brought the word ‘lodge’ with them, with the concept of forest law, into England after King William’s assent to the throne in 1066. As forests were named royal forests or parks with the intention of making them hunting grounds for the enjoyment of the Crown, lodges were built nearby or therein to shelter a custodian or a hunting party. In the Georgian period the upper classes took to fox hunting and the lodges fell into disuse or became country houses.

The masons of the Middle Ages built thatched, timber lodges at the work sites of the cathedrals and castles that would be easily torn down when the project was finished.[8] Schaw established permanent lodges for Scottish masons with his statutes, but the later Freemasons adopted the idea of the traveling lodge as they met in taverns or coffeehouses. The term likewise remained when the fraternity began building and meeting at permanent structures in the nineteenth century.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, the totally agricultural German invaders governed small divisions of territory, as communities survived only as local units. Cities had fallen, trade had decreased dramatically, and Roman architecture and roads fell into disuse and disrepair. The Christian Church, which had been violently persecuted under the early Empire, came to power in the early fourth century when Constantine made Christianity the state religion.

The Church was the single Roman institution that survived the German invasions, and as a powerful unifying force, it competed for centuries with secular political leaders across Europe. In 800 CE the Church crowned the Frank king Charles the Great, or Charlemagne, head of what it called the Holy Roman Empire, in an attempt to recreate the empire under the authority of the Church.

At about the turn of the first millennium of the Common Era, feudalism spread across Europe, developing political and economic hierarchies beginning with a king, descending to baron and then vassal. The barons were simply the most wealthy and powerful individuals in the land, who elected a king from among themselves, and subjected their lessers, the serfs (or freemen), to a life of labor and dependence upon their lord. Towns were owned by king, baron, or monastery. About this time merchants could amass significant wealth and the merchant guilds became established in Europe to regulate their industry. In this way the Crown could offer protection and monopoly in order to increase its own revenue.[9]

The Merchant Guilds: Origins of Speculative Freemasonry

About the tenth century merchant guilds appeared in Western Europe for mutual protection of goods and trade, and as industry specialization developed, craft guilds formed for the same reasons. Eventually, membership to a guild (also called a confraternity) was mandatory for anyone practicing a trade within a town or city.

Guilds regulated trade secrets, craftsmanship, pricing, and competition; they also regulated the morals of their members; participated in basic charities; and contributed to lay education, when education previously was the monopoly of the Church. The first important guilds of England were established during the reign of King Athelstan, as shown in the law code dated 930, as well as early masonic documents.

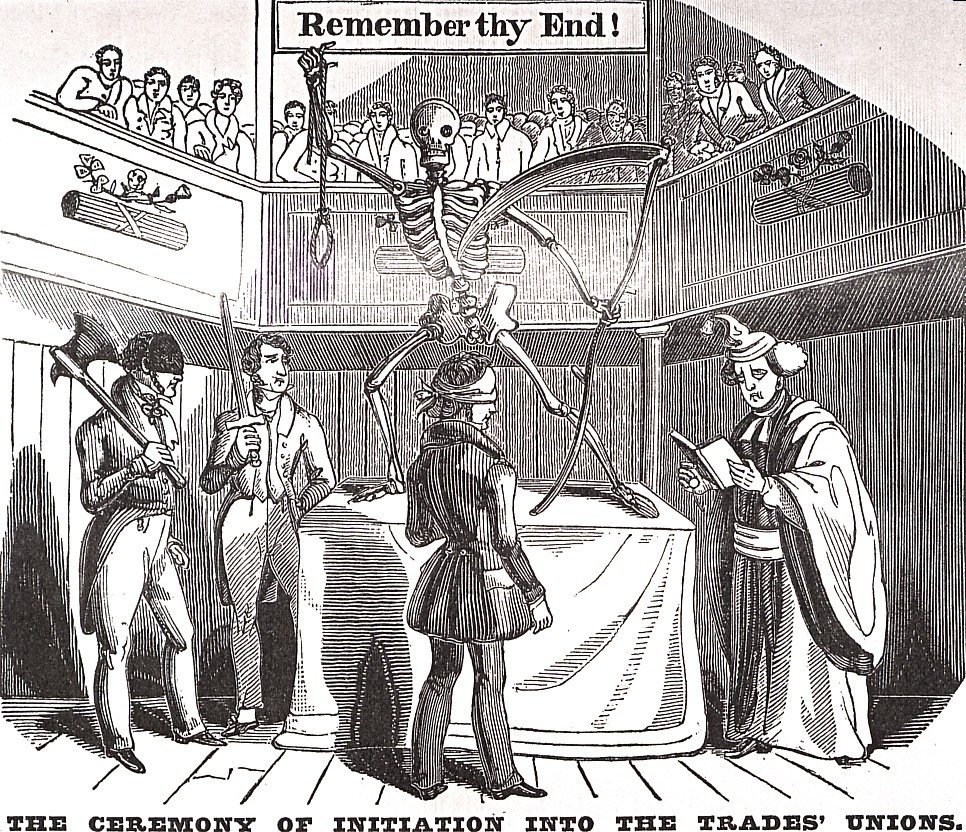

As early as the twelfth century, the clergy of the Roman Catholic Church formed religious guilds that among other things performed Miracle Plays for the masses, which taught lessons from the Holy Bible. From these guilds the trade guilds adopted the oath upon admission and the impetus to form charitable Benefit and Burial Societies.

Like other trade societies in the Middle Ages, the masons had their methods of identification, such as initiation ceremonies, secret handshakes and passwords. This was the only way to keep untrained craftsmen from posing as masters. These methods of identification, used by the early Freemasons, were known collectively in the early seventeenth century as ‘the Mason Word.’[10]

The trade guilds also adopted the practice of performing plays by the thirteenth century, which practice continued into the early seventeenth century. Morality plays put on for the public by various guilds centered on some aspect of the particular craft as featured in the Holy Bible. The shipwrights and fishmongers put on the story of Noah’s Ark, and the Goldsmiths focused on the story of the Magi at the birth of Christ, wherein the gift of gold was given to the infant.[11]

The natural subject of the masonic guild was the erection of King Solomon’s temple, which is described in the “Book of Kings” and the “Book of Chronicles.” Such plays bear some relation to the traditional rituals of Freemasonry.

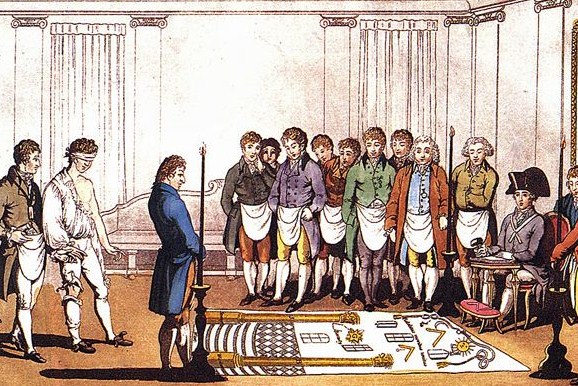

The working tools of the Freemason, like the apron and the gloves, were practical tools for the operative masons before they allowed non-operative (speculative) members into their lodges. There are no records of the ultimate origins of symbolic Freemasonry. It has been shown that the use of the lodge, apron, gloves, and working tools in masonry predates any spiritual symbolism attached to them in more recent times. Masonry, therefore, was not developed in order to represent a spiritual system of attainment. Rather, the spiritual aspect developed from the practical organization, or was adopted by it in the process of evolution.

As a few of the first known Freemasons belonging to speculative lodges were Rosicrucians learned in alchemy and other Hermetic arts, this early influence must be acknowledged. Thus the esoteric aspect of Freemasonry has different roots than exoteric Freemasonry. These roots must be traced through Hermeticism, which did not evolve as an unbroken chain through a secret society, but developed as a phenomenon throughout Europe in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, from origins in alchemists and philosophers of ancient Egypt, Classical Greece and Rome, and the Islamic Near East.

Alchemy in Freemasonry and Rosicrucianism

Operative and Speculative Freemasonry

Operative Masons were those who built the cathedrals and castles of Europe in the Middle Ages. Speculative Masons appeared in the sixteenth or seventeenth century, using in ritual symbols and allegory related to Masonry to teach virtue. The working tools of the mason that would later be used as symbols for philosophical teachings, like the apron and the gloves, were practical tools for the operative masons.

The exact connections between Operative and Speculative Masonry have not, at this time, been established. In their book World Freemasonry[12], John Hamill and R. A. Gilbert argue against the direct descent theory and suggest that more attention ought to be given the indirect descent theory. The authors describe the popular notion that Masonic guild lodges in the 1600’s began admitting non-operatives, for some reason not known today, which were called accepted masons. During this time there were fully operative lodges, transitional lodges, and fully speculative lodges.

The authors point out that the Schaw Statutes of 1598-9 in Scotland indicate the nature of operative lodges in Scotland, and surviving minute books show the development of ritual work and the admission of accepted masons, some lodges even becoming fully speculative by the eighteenth century. They point out that supporters of the theory of direct descent fail to consider the lack of such evidence in England, where operative lodges disappear by the sixteenth century, and no operative lodges are known to have made accepted masons.

Freemasonry in England seems to have originated in the seventeenth century with no connection at all to operative lodges. Hamill and Gilbert argue that no proof exists that Scottish operative lodges developed speculative ritual, or that their accepted Masons were anything more than honorary members of purely operative lodges.

Hamill and Gilbert go on to describe the indirect descent theory, epitomized in the work of Colin Dyer. This theory is based upon a knowledge of history and an examination of the Old Charges, evolving between the mid fourteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Regius Manuscript (c. 1390), which is the oldest extant document with direct Masonic references, and the Grand Lodge No. 1 MS of 1583. The Regius MS is a purely operative document, while the Grand Lodge MS contains material potentially relevant to both operative and speculative Masonry.

Historically, the authors explain, the Civil War period in England and preceding years was a time of great strife between opposing religious and political attitudes. A brotherhood founded on the principles of belief in God, Brotherly Love, Relief, and Truth, which banned discussion of religion and politics, might have been the natural creation of men who desired peace and harmony. The authors note that, for example, the initiation of Elias Ashmole in 1646 occurred in a lodge formed of both Royalists and Parliamentarians. They suggest that this society could have adopted the operative masons’ form of lodge as a framework for organization and their working tools as symbols of philosophical ideas, the central theme being the building of a better man. This is, the authors admit, a highly speculative theory that certainly deserves more research.

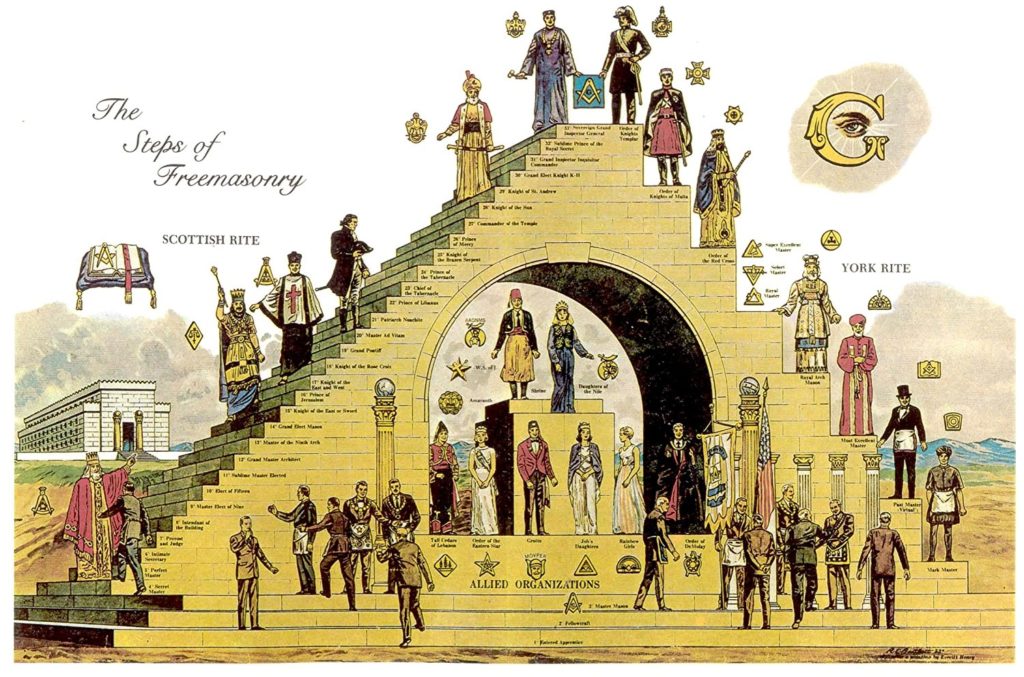

A third argument, put forth by J. A. Ness[13], asserts the development of Freemasonry in Scotland and its movement to England as a speculative fraternity. As stated above, records of fully operative lodges in Scotland making the transition to fully speculative form do exist. William Schaw, the master of works under King James VI and general warden of masons in Scotland, developed two codes at the end of the sixteenth century to organize and regulate the operative stonemasons’ trade in Scotland. These statutes first define the two grades of apprentice and fellow craft (or master mason), which would evolve into three grades nearly one hundred years later.

The Schaw Statutes of 1599 declare Edinburgh the first and principal lodge in Scotland; Kilwinning, the second “as is established in our ancient writings;” and Stirling the third lodge, “conformably to the old privileges thereof.”

In 1441, William Saint Clair, Earl of Orkney and Caithness, was made Patron and Protector of Freemasons in Scotland under King James II, a hereditary office that later held annual meetings at Kilwinning. Soon after the statutes were issued, Schaw signed, with a number of Scottish lodges, a charter recognizing William Sinclair of Roslin as patron and protector of masons, for King James VI had abandoned the practice of his forefathers of nominating officers for the Craft.

Transformations of Power and Wisdom

Under the feudal system advancements were made in agriculture until a food surplus allowed for the growth of towns and trade. In Italy and Germany the cities acquired their independence from feudal overlordship, while in France and England the towns received charters and certain liberties under the control of the Crown. By the late thirteenth century representative assemblies of the merchant classes had formed in government all across Europe.[14]

As the merchant class grew wealthier and more powerful, the restrictions of the guilds drove some manufacturers to relocate outside guild jurisdiction, and Henry VIII seized the property of a number of guilds as he did the monasteries.[15] These factors contributed to the downfall of the trade guilds. Records from this time show that Scottish Masonic guilds were accepting non-operatives into their societies, probably as patrons, and as the operative guild faded in relevance, the speculative organization endured.

During this time the Catholic Church was attacked by Protestant uprising throughout Europe. As the church completely lost its historical power, the beginnings of the scientific worldview were crystallizing in the persons of Nicholas Copernicus, Johannes Kepler, Galileo Galilei, Francis Bacon, Rene Descartes, and Isaac Newton. Modern science had arrived.

The English Civil War of this period began in 1642 and produced a Constitutional government, a representative government and elections. This helped perpetuate the culture of reason, religious toleration, social virtue, and advancement by merit begun with humanism and the Reformation. These would be adopted by the powerful parliaments of emerging capitalistic nations, which developed commercial empires by means of monopolistic trading companies and colonization.

The United Grand Lodge of England, the first grand lodge, at Freemasons’ Hall, Great Queen Street, London, England

The First Grand Lodge

The first Grand Lodge, the Grand Lodge of England, was formed on June 24, 1717. The Grand Lodge of England originated with four London lodges that met at the Goose and Gridiron Ale House, St. Paul’s Churchyard. The Grand Lodge was to meet annually for a Grand Feast, but no evidence exists to show that under the first Grandmaster, Gentleman Anthony Sayer, the Grand Lodge was to have any regulatory powers over the lodges in its jurisdiction of London and Westminster. When the Duke of Montagu assumed the position of Grandmaster in 1721, the jurisdiction of the Grand Lodge began to expand, quarterly meetings were held, and the body became regulatory.

Though a number of Grand Lodges were subsequently formed, the only real competitor of the premier Grand Lodge was that which called itself the Antients Grand Lodge, formed in 1751. This Grand Lodge was formed in protest of changes in ritual and custom in what they would call the Moderns Grand Lodge. The rift between the two Grand Lodges was healed in 1813 when the Grandmasters of each, brothers by blood, united the two as the United Grand Lodge of England. The Duke of Kent, leader of the Antients, conceded that the Duke of Sussex, head of the Moderns, should be first Grand Master.

The First Lodges on the Continent, Asia and America

The following account of the rise of Masonic lodges is not much more than a list of places and dates. It includes only Anglo-American Freemasonry, which deems itself “Regular Freemasonry” in contrast to Continental Freemasonry, Liberal, “clandestine” or “Irregular Freemasonry.” Unlike Regular Freemasonry, the latter does not require a belief in a Supreme Being, and it allows it lodges to engage in politics. Anglo-American Freemasonry also deems “Irregular” any Freemasonry that allows women to join, known as co-Freemasonic.

The Grand Lodge of Ireland, the second Grand Lodge to exist, was formed by 1725, and grew to govern Masonry upon the whole island. Ireland is noted here for the obscurity of the origins of its Freemasonry and for its role as the first organizer of a military lodge and its subsequent support of such lodges. It seems that the first lodge created on the continent was a lodge in Madrid, Spain, formed in 1728 around the Duke of Wharton, a past Grand Master of England. A lodge was formed in Calcutta, India, under the Grand Lodge of England in 1729.

By the 1730’s the Grand Masters of England were able to assign Provincial Grand Masters to constitute new lodges and help govern the new jurisdictions. English lodges or new Masonic jurisdictions early appeared in areas now known as Spain, Germany, Russia, the Netherlands, Switzerland, France, Italy, and Scandinavia, as well as India, Indonesia, North American Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia and Connecticut.

These early bodies founded many lodges of their own in seceding jurisdictions, emulating the Masters of some English lodges, who were given authority to create lodges in foreign jurisdictions, acting as “mother lodges” to them. For example, English Masons formed the English Lodge at Bordeaux in 1732, which eventually constituted a number of other lodges about France.

Finally, military lodges were given traveling warrants in order that members might meet wherever they were stationed. As military lodges began admitting civilians, stationary lodges were formed in the area even as the military moved on. Eventually, as most countries formed a Grand Lodge for their own territory, all lodges would submit themselves to either the newly constituted national Grand Lodge or, in rare cases, remain under the jurisdiction of the foreign Grand Lodge that created them.

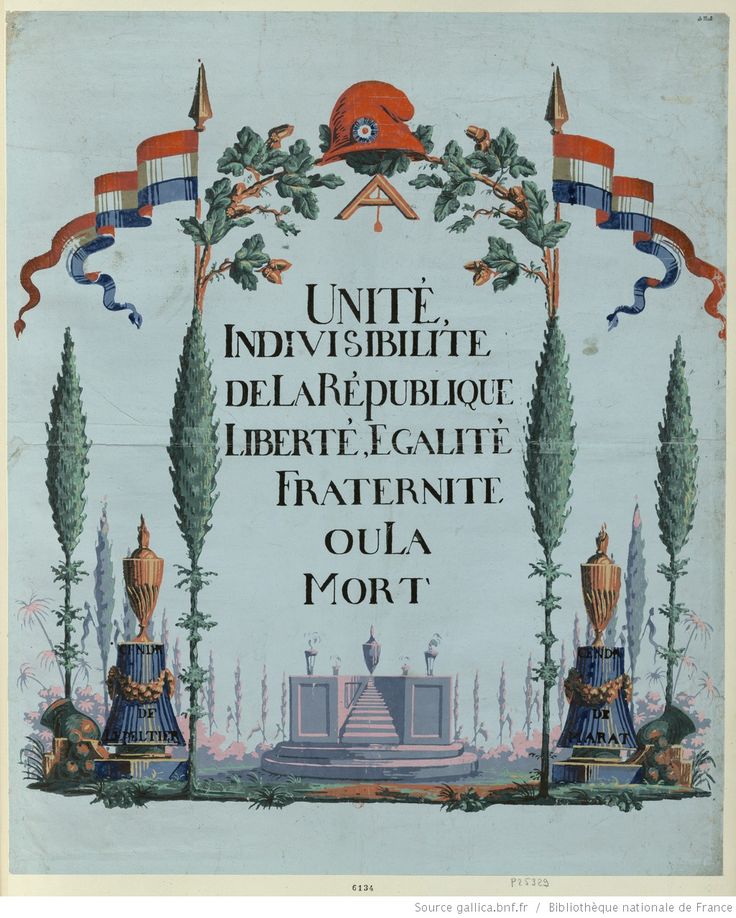

Liberty Leading the People

The Grand Lodges of Scotland and France

English and Scottish Jacobites founded the first Masonic Lodge in Paris in 1726, and Hanoverian supporters found a lodge in Paris three years later. This lodge was the first of many to receive an English warrant in the early 1730s. The Duke of Wharton, past Grandmaster of the premier Grand Lodge, became the first Grandmaster in France in 1728, and the first French Grandmaster was the Duke of Antin in 1738. The Grand Lodge of France was not recognized by the Moderns until 1766.

The Grand Lodge of Scotland was formed in the same year as the Grand Lodge of France, in 1736. In this year William Saint Clair of Roslin resigned his hereditary office due to the absence of any heir. At an assembly of Scottish Lodges at Edinburgh on November 30 his resignation was accepted and steps were taken for the regular election of a Grand Master, the first being William Saint Clair, himself. Thus was the present Grand Lodge of Scotland formed.[16]

Due to the complex developments related to the formation of French Masonic bodies and the relationships between these bodies, it is sufficient to note here the eventual creation in 1773 of the two most conspicuous of the many existing Grand Lodges in France, the Grand Lodge of France and the Grand Orient of France. France created lodges throughout Europe, Africa, and Brazil.

Freemasonry in the Germanic Countries and Russia

German Freemasonry began with English warrants in the 1730s and developed with French influence in the eighteenth century. Germany did not yet exist as a single nation, and this century saw the rise of a number of Grand Lodges, starting with the Grand Mother Lodge of the Three Globes in Berlin in 1740. By the 1930s there were no less than eleven Grand Lodges in Germany, which have since been reduced to five, and these have united under the institution of the United Grand Lodges of Germany. Germany assisted in establishing Grand Lodges in Bulgaria and Yugoslavia in the 1990s.

The first Provincial Grand Master of Russia and Germany was appointed by the Grand Lodge of England in 1731, but there is no proof of lodge activity in Russia until 1771, and the first Grand Lodge of Russia was not formed until 1776. Freemasonry has had a rather rocky existence in Russia, being outlawed and reinstated under various political regimes, and the present Grand Lodge of Russia was formed in 1995 with the help of French Masons.

In 1735 a lodge was erected at Stockholm, Sweden, according with French and English Masonry. Scandinavian Masonry, or the Swedish Rite, was developed in the 1750s, and was eventually adopted by the Nordic jurisdictions. The Grand Lodge of Sweden began in 1760. English Masons created the first lodges in Switzerland in Geneva in 1736. The Independent Grand Lodge of Geneva was formed in 1769, and soon French and German degrees were introduced, whereupon three new Grand Lodges were formed. The Grand Lodge “Alpina” of Switzerland united the different Grand Lodges in 1844.

The first Danish lodge, St. Martin Lodge, opened in Copenhagen in 1743 and was followed by the creation of English and German lodges. Six years later an English Provincial Grand Lodge was formed, which recognized St. Martin Lodge with a warrant. The National Grand Lodge of Denmark constituted the National Grand Lodge of Iceland in 1951. In 1749 the first lodge in Norway was erected under English auspices. Lodges were governed by a Swedish Provincial Grand Lodge from 1814 to 1891, when the Provincial Grand Lodge became the Grand Lodge of Norway.

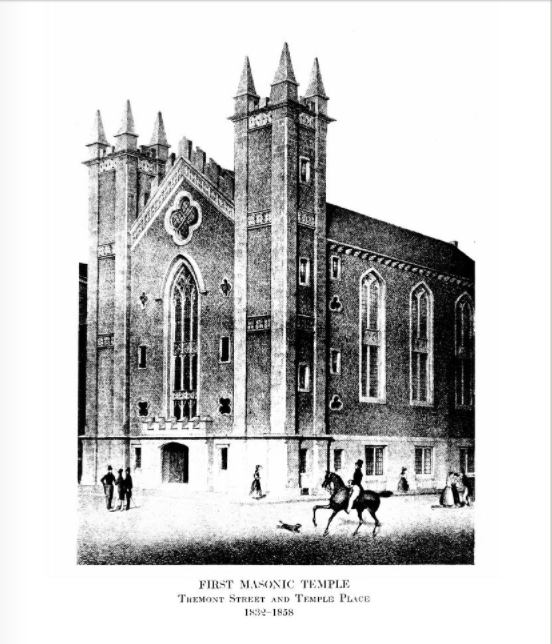

The temple on Tremont Street of Saint John’s Lodge, Boston, Massachusetts, the first Masonic lodge in the Colonies (1733)

Early North American Lodges

It must be remembered that most members of early non-European lodges were Europeans living or working abroad. In the case of North America natives were not invited into the Craft until the late eighteenth century. The first chartered lodge in the American colonies met at the Tun Tavern in Philadelphia probably before 1730, and there was, at least in name, a Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania by 1731. In 1733 the Provincial Grand Lodge of New England in Boston, Massachusetts under the Premier Grand Lodge of England, became the first Grand Lodge in what would later become the United States of America.

A charter was issued for the First Lodge, later renamed St. John’s Lodge, and by 1734 the Provincial Grand Master officially held all of North America under his authority under St. John’s Grand Lodge. By 1776 lodges had been chartered in Connecticut, New Hampshire, New Jersey, the Carolinas, Pennsylvania, and other North American territories. There existed a Provincial Grand Lodge of North America based in New York in the 1730s, but the first records of lodge activity in the colony belong to St. John’s Lodge from 1757.

There was a Solomon’s Lodge that met in Savannah, Georgia probably in 1735, and the Royal Exchange in Virginia supposedly met in the 1730s, each chartered (in the latter case, not until 1754) by the Grand Lodge of England. The Virginia Grand Lodge in 1778 and the Massachusetts Grand Lodge in 1790[17] claimed independence from the Grand Lodge of England, which helped to promote such action from other American jurisdictions after the Revolution. Efforts to form a Grand Lodge of the United States never met with success due to local differences and power jealousies.

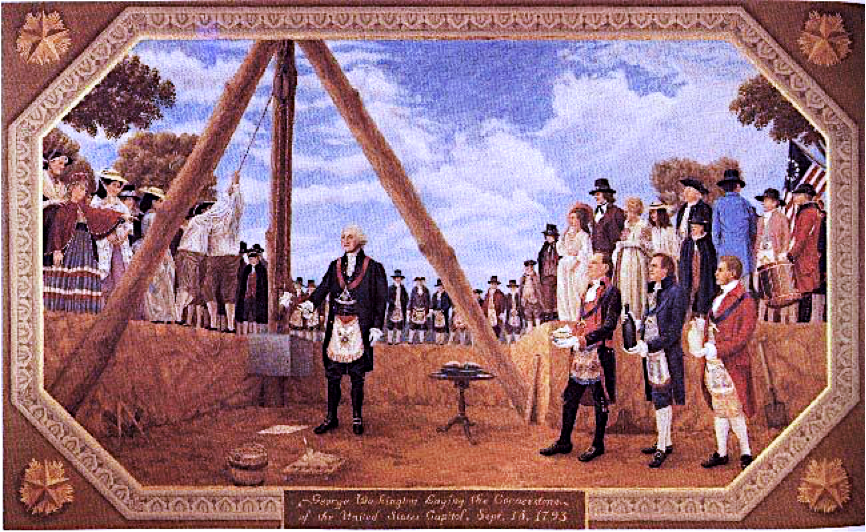

George Washington, Freemason, Laying the Cornerstone Ceremony at the Site of the Future Capitol, 1793

Global Freemasonry

The success of Freemasonry in many areas has ebbed and flowed due to political and other conditions inimical to the ideals or operations of the Craft. The countries surveyed below provide plentiful examples of this situation, but a detailed account is inappropriate here. It is sufficient to note the first flowerings of the fraternity upon the various regions.

The first lodges in Central and South America appeared in the 1820s in Mexico, Columbia, Brazil, Venezuela, and Haiti. Early Mexican lodges were chartered by Spanish and United States Masons. In Columbia and Venezuela the early English and Scottish lodges faded away but a Grand Orient of New Granada was formed at Cartegena in 1827, and Venezuela has maintained its Grand Lodge from 1824. The Grand Orient of Brazil has a history of schism and competition with state Grand Lodges. In the early eighteenth century Masonic lodges were working in Estonia, Latvia, Greece, and Turkey, created via various European countries.

Freemasonry traveled from Germany into Austria in 1742 and from there to Bohemia; lodges were meeting in Prague by 1775. Germany and Austria also brought the Craft to Transylvania in 1749, but all of these efforts were soon suppressed by the Austria-Hungarian Empire,[18] and Masonry did not begin to get a hold in the area until late the next century. The first Russian lodge on record was the Perfect Unity Lodge #414 at St. Petersburg in 1771. The National Grand Lodge of Russia was formed in 1776.

The first lodge in the Netherlands met in The Hague in 1734, and ten lodges united to form the Grand Lodge of the Netherlands in 1756, which was recognized by the Grand Lodge of England in 1770. The Netherlands has had many lodges warranted abroad, including lodges in South Africa, Zimbabwe, the Dutch West Indies, and Indonesia. Freemasonry has since been outlawed in Indonesia.

The Netherlands chartered the first lodge in Africa in 1772 at Cape Town, called Goede Hoop Lodge #18. Lodges in many parts of Africa, usually formerly colonized areas, have been chartered under various European Grand Lodges, especially the English and French, and a number of African countries have formed their own Grand Lodges since the nineteenth century. An excellent summary of African Freemasonry may be found in Henderson and Pope’s Freemasonry Universal.

Freemasonry found its way into the Middle East in the mid-nineteenth century. Scotland found lodges at Yemen and Palestine during this time, and though a few other lodges have manifested in other countries, only Lebanon, Israel and Iran can claim to have a Grand Lodge, and Iran meets in exile in Boston, Massachusetts.

As mentioned above India had its first lodge in Calcutta in 1729, and its second lodge, Lodge Star of the East #67, formed in 1740, still meets. The Swedes erected lodges in China in the mid eighteenth century, and since that time other Europeans have helped create lodges throughout Asia. Masons met in the Philippines from the 1760s, encountered opposition from the government in the first half of the nineteenth century, and after about two decades of general acceptance, formed the Grand Lodge of the Philippines. This Grand Lodge played an important role in the creation of Grand Lodges in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Japan. Other notable Grand Lodges in Asia include those of Singapore and Malaysia.

Universal and Global Principles

The above account is necessarily an extremely simplified view of the origins of Freemasonic development around the world. Throughout many times and places the Craft has gained a foothold in a country only to be suppressed officially or completely after a number of years. Often, the fraternity is reborn after a change in government or other conditions. The stories are manifold and inevitably unique.

Looking back on the history of the development of Freemasonry across the globe it is interesting to notice how quickly the ideas and practices spread across national and cultural borders. Within nearly fifty years of the creation of the first Grand Lodge in London, lodges were formed over Western and Eastern Europe, Africa, the Americas, India, and the Far East. From the obscure origins of the “speculative” Masonic lodges in Great Britain, which obviously cultivated an influence from actual operative lodges of the European Masonic guilds, a global entity had formed almost spontaneously.

Freemasonry is meant to be universal. It stands beyond race, religious creed, and political persuasion. Anderson’s Constitutions,[19] defining the qualifications for a Mason, tells us that “The persons admitted members of a Lodge must be good and true men, free-born, and of mature and discreet age, no bondmen, no women, no immoral or scandalous men, but of good report.”

As regards religion, “But though in ancient times Masons were charg’d in every country to be of the religion of that country or nation, whatever it was, yet ‘tis now thought more expedient only to oblige them to that religion in which all men agree, leaving their particular opinions to themselves; that is, to be good men and true, or men of honour and honesty, by whatever denominations or persuasions they may distinguish’d…”

The text further explains that even a member who disagrees with the present government, so long as he is not convicted of a crime, cannot be expelled from the Lodge. George Washington, the United States of America’s foremost Freemason, said of Freemasonry, “Your sentiments on the establishment and exercise of our equal government are worthy of an Association whose principles lead to purity of morals and are beneficial of action… I shall be happy on every occasion to evince my regard for the fraternity.”[20]

The early Freemasons anticipated the United States Declaration of Independence and the United Nations Charter in maintaining that these principles, which “lead to purity of morals and are beneficial of action” rest on a self-evident or fundamental basis. It is not surprising that a fraternity that from its origins espoused universal moral principles found itself quickly spread over the entire face of the inhabitable earth.

The history of the development of global Freemasonry has been important since the Craft began to be practiced beyond Britain. Freemasonry spread across the globe largely on the impetus of the growth of the British Empire in the nineteenth century. The ‘International Compact’ of 1814 determined that the English, Scottish, and Irish Grand Lodges would mutually respect their relative jurisdictions, and would warrant lodges only in their own jurisdictions or where no Grand Lodge existed. It is customary even today, however, to allow a lodge that prefers it to remain under its original jurisdiction in an area where a new Grand Lodge has been formed.

According to the 2004 List of Lodges Masonic, published annually by Pantagraph Printing and Stationary Co., approximately 175 Grand Lodges exist throughout the world. Browsing through Freemasonry Universal[21] one counts about 150 countries that support at least one Masonic Lodge of their own, and it is interesting to note the number of lodges that have presumably gone underground or have been abolished by antagonist governments, or which no longer exist for various reasons.

A well-documented record of Freemasonry’s development will aid in showing her historically cosmopolitan position. Freemasonry as it is known today is nearly three hundred years old, but her basic principles, embodied in the ancient charges, remain unchanged. Freemasonry’s unique system of morality continues to provide a solid base for universal moral instruction. There exists no equal to this time-tested model, which might and ought, therefore, to serve in some capacity in the improvement of international affairs in general. It is the function and duty of the Craft to provide far-extending epistemological and ethical standards to a world that is, and has long been, struggling in darkness for the same.

Ground plan of Solomon’s Temple

BIBLIOGRAPHY

[1] Ingrid D. Rowland, Vitruvius, Ten Books on Architecture, Cambridge University Press, University Printing House, Cambridge, U.K., 1999, p 7.

[2] Ibid., p. 35 (Book 2, Ch. 2.1).

[3] Albert G. Mackey, Mackey’s Revised Encyclopedia of Freemasonry, The Masonic History Company, Chicago, Illinois, 1929. Vol. I, pp.221-226.

[4] Leader Scott, The Cathedral Builders: the Story of a Great Masonic Guild, Sampson Low, Marston and Company, Limited, London, 1899.

[5] Christopher Flannery, “Liberal Arts and Liberal Education, On Principle,” V6N3, June 1998.

[6] The Regius Poem, Masonic Book Club, 1970, pp. 2-3. (See the English translation by Roderick H. Baxter, “The Regius Poem,” Masonic Book Club, 1970, pp. 52-53.)

[7] The Regius Poem, Masonic Book Club, 1970, p. 23.

[8] “Sources for the History of Lodges,” 31 March, 2004, www.building-history.pwp.blueyonder.co.uk/Buildings/Lodges.htm.

[9] Edward Cressy, Outline of Industrial History, MacMillan and Co., 1925, p.29.

[10] David Stevenson, The First Freemasons: Scotland’s Early Lodges and Their Members, Aberdeen University Press, 1988, p.5.

[11] Frederick Armitage, The Old Guilds of England, Weare & Co., 53 & 54, King William Street, E.C. 4. 1918, p.25

[12] John Hamill and R.A. Gilbert, World Freemasonry, an Illustrated History, The Aquarian Press, London, 1991.

[13] J.A. Ness, The Antient Mother Ludge of Scotland, Mother Kilwinning No. 0, Printed by Print2000 Ltd., Glasgow, 1995.

[14] Jean Reeder Smith & Lacy Baldwin Smith, Essentials of World History, Barron’s Educational Series, Incorporated, 1980, pp. 60-71.

[15] Edward Cressy, Outline of Industrial History, MacMillan and Co., 1925, pp. 35-36.

[16] Albert G. Mackey, Mackey’s Revised Encyclopedia of Freemasonry, The Masonic History Company, Chicago, Illinois, 1929. Vol. 2, 1958, pp. 898-899.

[17] Steven C. Bullock, Revolutionary Brotherhood, Freemasonry and the Transformation of the American Social Order, 1730-1840, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill & London, 1996, p.115.

[18] Kent Henderson and Tony Pope, Freemasonry Universal, a New Guide to the Masonic World, Global Masonic Publications, Williamstown, Victoria 3016, Australia, 1998. Two Volumes, p.257.

[19] The Constitutions of the Freemasons (Reprint of Anderson’s book by Benjamin Franklin), Masonic Book Club, Bloomington, Illinois, 1971, pp. 48-50.

[20] Washington Centennial Committee of the Grand Lodge of Virginia, Official Souvenir of the Centennial of the Death of Worshipful George Washington, Past Master Alexandria Lodge, No. 22, A.F. and A.M., 1799-1899, George T. Parker & Co., 400-402 Sixth Street N.W., Washington, D.C., p.159.

[21] Kent Henderson and Tony Pope, Freemasonry Universal, a New Guide to the Masonic World, Global Masonic Publications, Williamstown, Victoria 3016, Australia, 1998, Two Volumes.